Patients are often reminded they should complete each course of antibiotics to prevent bacteria becoming drug-resistant – but this advice is a “myth” that should be dropped, experts have argued.

Wednesday 26 July 2017

Patients are usually advised to complete the prescribed course of antibiotics Getty

Official guidance from the NHS says “it’s essential to finish taking a prescribed course of antibiotics, even if you feel better, unless a healthcare professional tells you otherwise”.

Now scientists have challenged this piece of received wisdom, which they say is not backed by evidence, warning unnecessary exposure to antibiotics could in fact make resistance worse.

It may in fact be best for people to stop taking the drugs when they feel better, wrote a team of researchers in the British Medical Journal(BMJ).

However, GPs have indicated they do not intend to remove advice to patients to finish their antibiotics, as “changing this will simply confuse people” and could cause patients to fall ill again, because an improvement of symptoms does not always mean an infection has been eradicated.

Oxford professor Tim Peto said he was taught about the importance of finishing a course of antibiotics as a medical student, but when he began discussing the origin of the idea with his colleagues, “no one could work out where it came from”.

“This is slow-motion fake news. It went through word of mouth, before the internet,” he told The Independent. “Yes, it’s an urban myth.”

Professor Peto and the group of experts led by Professor Martin Llewelyn, from Brighton and Sussex Medical School, traced our concern over giving too little treatment to the period of very early antibiotic innovation.

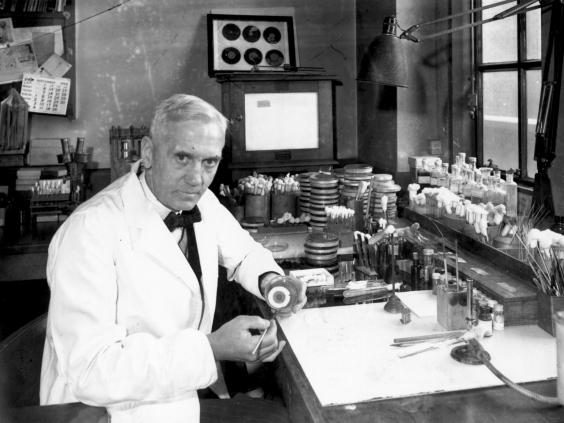

It may be attributable to unproven speculation by Alexander Fleming, the biologist who discovered penicillin, they said.

When he accepted the Nobel Prize for his work in 1945, Fleming, who had noted that bacteria could mutate when exposed to the new drugs, delivered a vivid speech describing an imaginary patient with a throat infection who had failed to complete his course of antibiotics.

This was an “emotive story” in which “the man got better, resistance emerged, then his wife got the bug and died,” said Professor Peto. “We think it became embedded in people’s minds and became part of the ‘known facts’.”

It has now been shown that the bacteria Fleming named in his tale, Streptococcus pyogenes, never actually developed resistance to penicillin, casting his hypothesis further into doubt.

Antimicrobial resistance is caused when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change through continued exposure to drugs, which then become ineffective against them.

Over time, excessive use of antibiotics could lead to minor infections causing serious health complications, making surgery and treatment for diseases such as cancer much riskier.

England’s chief medical officer Dame Sally Davies has warned that 50,000 people die each year in Europe and the US from infections that have developed resistance against antibiotics.

“The relation between antibiotic exposure and antibiotic resistance is unambiguous both at the population level and in individual patients. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic use is therefore essential to mitigate antibiotic resistance,” wrote the researchers.

They also recommended that doctors should be able to change the duration of antibiotic treatment based on the patient’s responses to the medication.

But Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, chair of the Royal College of GPs, said recommended courses of antibiotics “are not random” and are tailored to individual conditions.

“In many cases courses are quite short, for example for urinary tract infections, three days is often enough to cure the infection,” she said.

“We are concerned about the concept of patients stopping taking their medication mid-way through a course once they ‘feel better’, because improvement in symptoms does not necessarily mean the infection has been completely eradicated.

“It’s important that patients have clear messages and the mantra to always take the full course of antibiotics is well known – changing this will simply confuse people.

“We agree with the researchers that more high quality, clinical trials are needed – and when guidelines are updated, they should take all new evidence into account. But we’re not at that stage yet.”

Professor Stokes-Lampard added that while antibiotic resistance was one of the biggest global challenges, “we cannot advocate widespread behaviour change on the results of just one study”.

Alison Holmes, director of Infection Prevention and Control at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, said the “dogma” of telling patients to complete the course of antibiotics “has been pervasive and persistent.”

“Whilst there has been an enormous focus on developing new agents to combat AMR, there is just not enough existing data and current research to optimise the prescribing of existing antibiotics in terms of dosage and duration,” she said.

“The ‘complete the course’ message also directly conflicts with the societal messages regarding the changes needed in behaviour and attitudes to minimise unnecessary exposure to antibiotics.”

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/antibiotic-courses-complete-bacterial-resistance-worse-medical-myth-scientists-doctors-pills-a7861351.html