Mosquitoes armed with virus-fighting bacteria sharply curb dengue infections, hospitalizations

Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes in the lab

A strategy for fighting dengue fever with bacteria-armed mosquitoes has passed its most rigorous test yet: a large, randomized, controlled trial. Researchers reported today dramatic reductions in rates of dengue infection and hospitalization in areas of an Indonesian city where the disease-fighting mosquitoes were released. The team expects the World Health Organization (WHO) to formally recommend the approach for broader use.

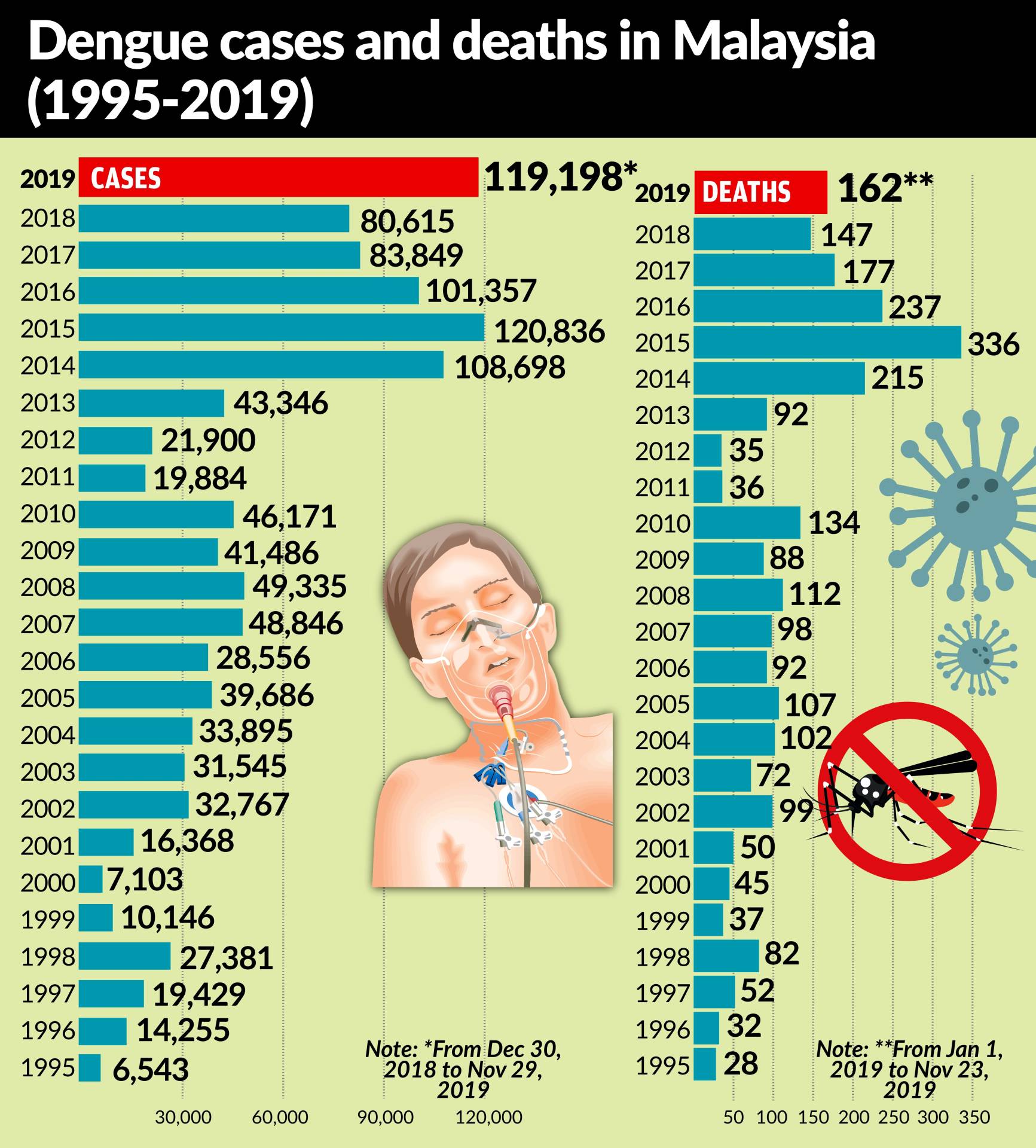

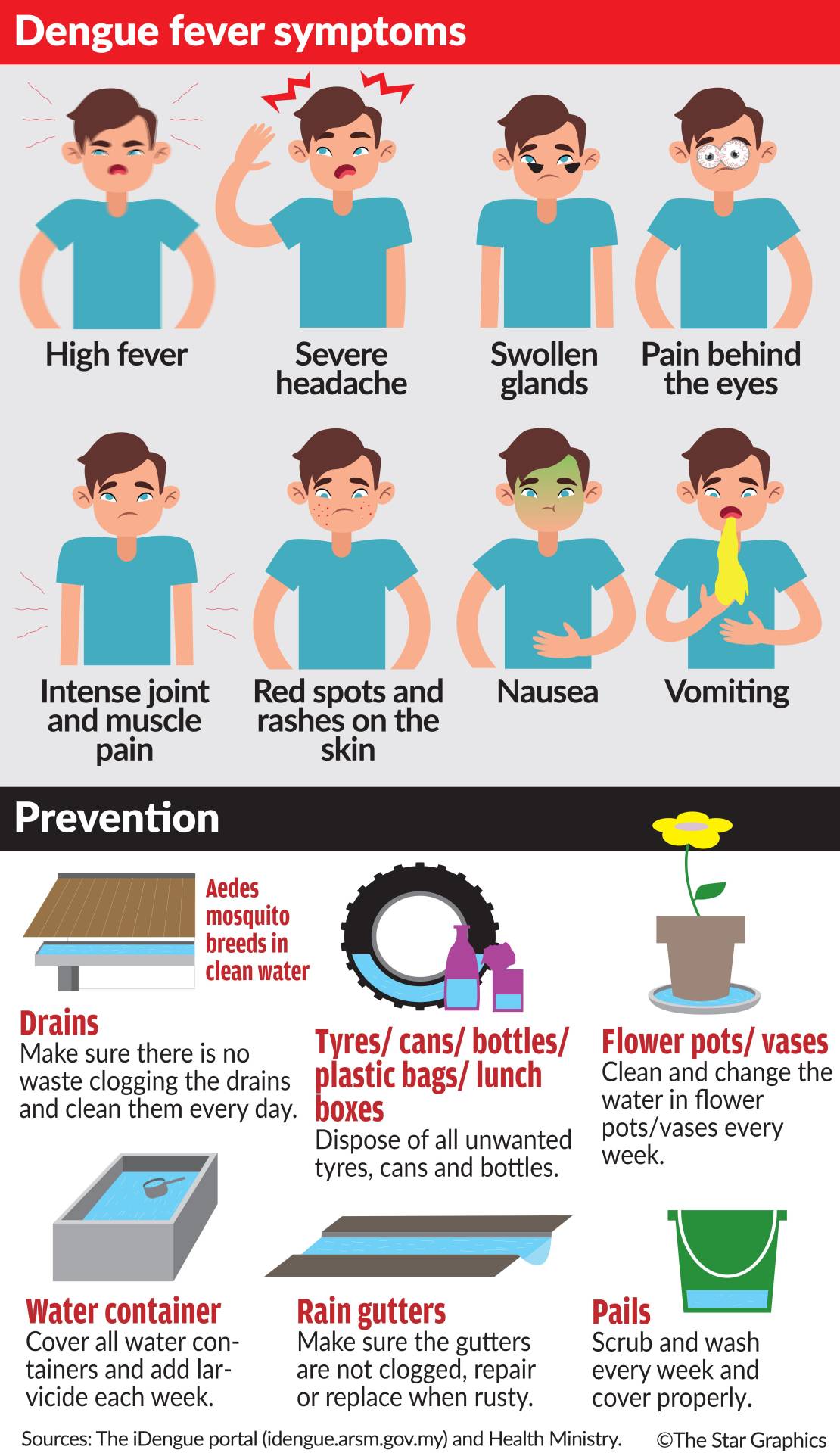

The findings are a “breakthrough” that brings the approach “much closer to … being an official strategy to control dengue,” says Ewa Chrostek, an infection biologist at the University of Liverpool who was not involved with the work. WHO estimates there are 100 million to 400 million infections per year with dengue, which can cause high fever and severe joint pain.

The bacterium Wolbachia pipientis naturally inhabits many insects, though not Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, the main transmitter of dengue virus. In A. aegypti cells, the bacterium can block viruses, including dengue, from replicating, making the insects less likely to spread disease when they bite humans. That has made the microbe a promising strategy for fighting dengue. In tropical regions, where mosquito-borne viruses are common, other strategies such as insecticides have failed to fully control the disease.

A few previous studies have found that areas where Wolbachia mosquitoes were released had lowered rates of dengue compared with nearby untreated areas, or with historical infection rates. But, “The global scientific community was looking for gold-standard evidence, and that means a randomized trial,” says Cameron Simmons, an infectious disease researcher at Monash University, Melbourne, and an investigator with the nonprofit World Mosquito Program (WMP), which conducted the new study.

For that gold-standard trial, the researchers divided a 26-square-kilometer area in Yogyakarta, Indonesia—an urban area home to about 300,000 people—into 24 clusters. In 12 of those clusters, the team set out containers of Wolbachia-carrying mosquito eggs every 2 weeks for 18 to 28 weeks. The microbe eventually spread through the local mosquito population: Ten months after releases started, the prevalence of Wolbachia among mosquitoes in the treated clusters had climbed to 80% or higher.

The team then recruited study participants who came to primary care clinics in the city with a fever. Of the patients who lived in treated clusters, 2.3% tested positive for dengue virus, versus 9.4% of those from control areas—a 77% reduction in infections, the team reports today in The New England Journal of Medicine. Beyond the drop in infections, which WMP announced in August 2020, the researchers also found an 86% reduction in hospitalization for dengue among study participants.

“That’s really the big thing,” Simmons says. “It’s the weight of hospitalization … that really stretches health systems.”

The paper offers other encouraging details, Chrostek says: The Wolbachia strain, known as wMel, was effective against all of the four main subtypes of dengue virus that infect humans. And computer models determined the more exposure a person had to Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes—calculated based on Wolbachia prevalence both near their home and in clusters where they had recently traveled—the lower their risk of dengue. Wolbachia infection gradually spread to mosquitoes in the nontreated clusters during the trial, and in January, after the trial had ended, WMP released Wolbachia mosquitoes in those clusters, aiming to further drive down or even eliminate dengue in the area.

In December 2020, WMP presented its data to a WHO advisory group, and the organization is now developing a recommendation for Wolbachia mosquitoes as a method of dengue control. WMP is also seeking a WHO “prequalification” that would make it eligible for investment from U.N. agencies to support future releases, Simmons says. He notes that the cost of the approach is already less than $10 per person protected, and WMP aims to get that cost below $1.

Still, Ary Hoffmann, a biologist at the University of Melbourne who worked with a predecessor of WMP on earlier Wolbachia releases in Yogyakarta, says it’s important to keep monitoring levels of the bacterium and rates of dengue in the experimental areas. Wolbachia levels have remained high for 10 years at sites of some previous mosquito trials without releasing more insects. But Hoffmann notes that the genome of the mosquitoes, the bacterium, or the dengue virus could potentially evolve to reduce the level of protection Wolbachia confers. “This is a great technology,” he says, “but we need to think about the longer run.”