The COVID vaccine rollout is underway, with Australians lining up to get their jabs. But what if you have already had COVID-19? Is it still a good idea to get vaccinated?

March 25, 2021 5.51am AEDT

Cassandra Berry, Murdoch University

People who have had COVID will still benefit from having a COVID vaccine. Here's why.

Although natural exposure to the virus stimulates immunity, we don’t yet know how long this immunity will last. And people will vary in their ability to mount a protective immune response.

Even if you’ve had COVID-19, you should still get vaccinated. A COVID vaccine may offer more reliable and sustained immunity than a previous infection. At the very least, it will add an extra layer of targeted protection.

Here’s how our immune response works after a natural infection versus a vaccine.

From B cells to neutralising antibodies

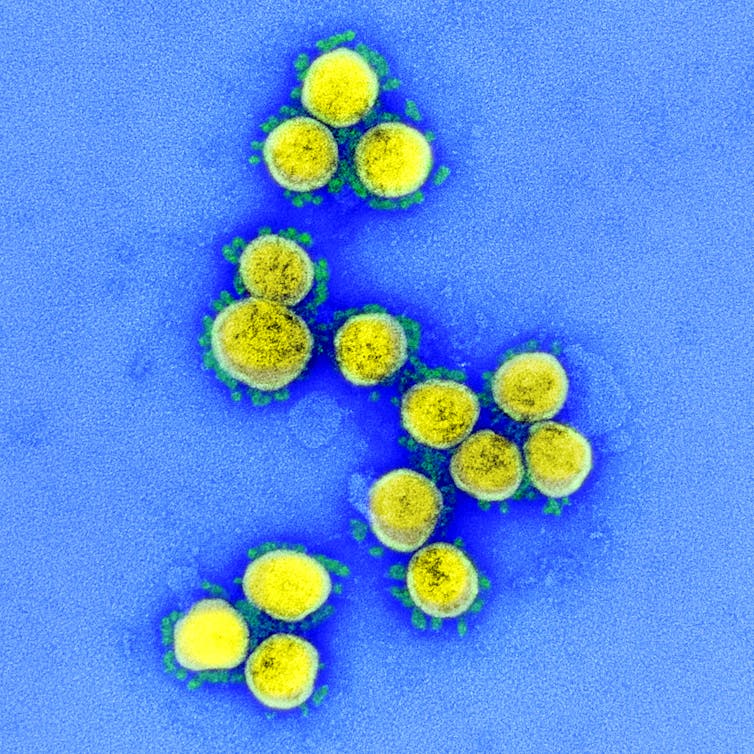

Soon after becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), our immune cells (T cells and B cells) activate. Activated B cells produce so-called neutralising antibodies. These antibody-secreting cells defend our bodies against the infection by making antibodies that bind to spikes on the virus surface, and block the virus from entering our cells.

Neutralising antibodies spill over into the bloodstream and travel around the body looking to mop up virus. After the infection has resolved, these activated B cells calm down and transition to a resting state. They move from our blood to our lymph nodes and bones. These so-called memory B cells survive for decades, along with help from memory T cells.

But they need a nudge once in a while to ensure they’re ready to kick into gear if we’re exposed to an infection.

Our immune cells rely on memory

When we’re re-exposed to a virus, or receive a vaccine booster, these memory cells awaken, become activated and produce large amounts of antibodies much faster. This immune memory reduces the risk we’ll become infected with SARS-CoV-2. But if we do, it allows for quicker healing from COVID-19.

Sustained neutralising antibody levels indicate a good degree of protection against SARS-CoV-2. How long we hang onto natural immunity after COVID-19 is variable and depends on viral, human and environmental factors. For example, the viral variant can make a difference, along with our genes, underlying health conditions, and age.

These factors can affect our neutralising antibody levels, which can wane over time to dip below protective levels.

As COVID-19 hasn’t been around for a particularly long time, it’s difficult to know how long natural immunity generally lasts. However, antibodies and immune memory appear to last for at least two months.

For patients who have recovered from SARS, a related coronavirus, research has shown they maintained antibodies for up to two to three years following infection.

Immune responses to a vaccine

Again, because of the short time frame, we have limited data on sustained antibody responses following vaccination. But immunity appears to be strong three months after the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

With COVID-19 vaccines, certain variable factors have been targeted, in a way they can’t with natural infections. For example, considerations like the dose size and the time between doses are all established to confer optimal immunity.

As we continue to monitor people who have received the COVID vaccines, we’ll develop a better understanding of protective immunity and its longevity.

Staying on top of variants

Natural immunity from infection may protect against other variants to some degree, but vaccines will play a crucial role as the virus continues to mutate.

It may be necessary to get regular boosters of the COVID vaccine until the pandemic is under control. This will provide protection against variants our pre-existing antibodies may not be able to neutralise.

Boosters enhance our broad immunity to parts of the spike proteins shared between different virus variants. Antibodies produced to these common regions can neutralise the virus and stop infection.

We saw this to a limited extent in people who had common cold infections with other coronaviruses before COVID-19.

Only one jab? Vaccines as a cure for long COVID?

There’s been some research suggesting people who have had COVID may only need one dose of the vaccine to be protected.

For people who have had COVID, one dose may serve to top up their antibodies to protective levels. This is because they’re starting on a stronger footing in terms of their antibody levels and immune memory, compared to people who haven’t had the virus.

But experts in Australia still recommended two doses, regardless of whether you’ve had COVID.

Read more: Why we'll get COVID booster vaccines quickly and how we know they're safe

Meanwhile, reports have indicated people experiencing long COVID may also benefit from vaccination. We’re not sure how this happens, but symptoms may improve with clearance of any hidden virus reservoirs from the body. Research into this phenomenon is ongoing.

At the end of the day, when the vaccine is available to you, you should get vaccinated, even if you’ve had COVID-19. While the vaccine is likely to protect you, it’s also important to protect others, as we look towards a goal of herd immunity.

CoronavirusImmune responseneutralising antibodiesCOVID-19COVID vaccinesImmune memory

https://theconversation.com/do-i-still-need-to-get-a-covid-vaccine-if-ive-had-coronavirus-157599