This post is on Healthwise

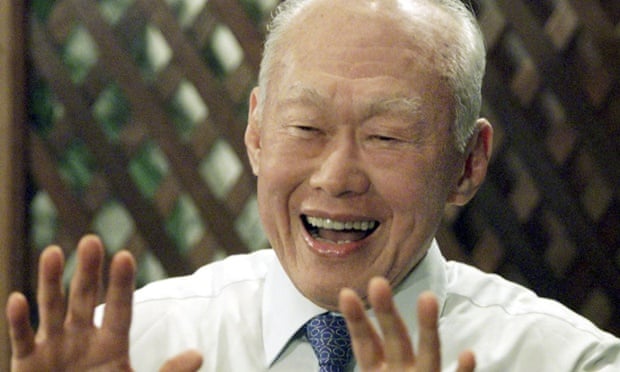

As first prime minister of Singapore, serving for three decades until 1990, and a continuing cabinet presence for the two that followed, Lee Kuan Yew, who has died aged 91, was a man whose story reflected his times. A relentless nation-builder like Tito, an instantly identifiable symbol like Haile Selassie, Lee also had a third dimension, especially in western eyes – statesman, philosopher king, embodiment of the wisdom of the east.

Lee’s role in and articulation of events from the Pacific war and the Japanese occupation of Singapore till leaving politics completely in 2011 made him a pivotal figure of the modern world. To many he became the embodiment of the orderly transition of a region from western dominance to neo-Confucian success. Yet experience had taught him to be a pessimist, which drove him to work harder, to be more ruthless.

Lee himself may not have changed the world outside little Singapore very much. Indeed, his greatest apparent achievement, the creation of a viable independent state, was the outcome of his biggest failure – Singapore’s expulsion from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, two years after the organisation’s inception. His first vision of Singapore’s future, as part of a multicultural Malaysia, may prove in time to have been the correct one, but he can be at least partly judged by the achievement of his second vision for Singapore, the prosperous, prickly and obsessively hygienic city state.

He did not create modern Singapore’s prosperity. The city state thrived naturally in a region of economic growth and rapid development of world trade. However, he certainly created the image of the state in his own likeness.

Being liked was not part of his agenda. A combination of high intelligence and unswervable determination were Lee’s characteristics, and he transferred them, at least superficially, to modern Singapore. Without him, it may in time go a different way, more reflective of its multiracial background and potentially precarious existence. But while he was alive few dared think, let alone put forward, alternative visions.

Lee has been described as many things. To Chinese, particularly during his days fighting Chinese chauvinism in the name of a multiracial Singapore identity, the Cambridge-educated lawyer brought up to believe in English education if not in British institutions, Lee was a “banana” – yellow on the outside, white inside. However, later in life, as Chinese identity and Confucian attitudes emphasising education, discipline and hierarchy became more important, he would be criticised for presenting himself as a fount of wisdom, a convincing articulator of modern Asia to western audiences, while actually behaving with all the intolerance of a Chinese emperor. At his worst, he could combine imperial hauteur with extraordinarily petty spite, relishing the destruction of irritating but unthreatening critics. At his best, he had an incisive mind and clear political judgment. For an avowed elitist, he had a remarkable ability to talk to a crowd.

Born in Singapore, Lee was the eldest son of Lee Chin Koon and Chua Jim Neo, members of a comfortably off but not rich Straits Chinese family. The Straits Chinese were those who had been settled in the region for many years, losing much of their Chinese identity both to the language and institutions of their British rulers, and to the Malays, their neighbours whose tongue was the lingua franca of south-east Asia.

The young Harry, as Yew was known in the English-language environment of the time, came first in Malaya in the Senior Cambridge exams (the equivalent of A-levels) of 1939 and was destined to go to Britain to study law. But the second world war intervened and he had to go to the local Raffles College instead, where he acquired some basic economics, and met his future wife, Kwa Geok Choo. The delay in going to Britain was but a minor inconvenience compared with the sudden and humiliating British surrender of Singapore in February 1942. Lee described his own initial humiliation at the hands of Japanese troops as “the single most important event of my life”.

Little is known of his actual role during the occupation, other than that he learned Japanese (he had a remarkable facility for languages), worked for Domei, the Japanese news agency, and may in the latter days of the war been of help to the British. The obscurity with which this period has been shrouded subsequently gave rise to much speculation about his relationships with the British and the Japanese. But he saw enough of British failures not to want to ape them, and enough of Japanese brutality – mostly directed against the recent migrant Chinese than against the more compromising Straits Chinese – to resent them. As he later wrote, he emerged from the war “determined that no one – neither the Japanese nor the British – had the right to push and kick us around”.

Combining drive with connections, he got himself to Britain in 1946 to study at the London School of Economics. But deciding he needed to aim higher, he talked his way into Fitzwilliam Hall, Cambridge, and graduated in 1949 with a starred first in law. His wife-to-be, whom he married the following year, also got a first.

It was also during this time that he began to develop ambitions beyond returning home to a prosperous legal career. He recognised that the British could not recreate the comfortable, colonial Singapore of prewar days. Nationalism, socialism and communism were in the air. In a speech in 1950 to the Malayan Forum in London, he said: “The choice lies between a communist republic of Malaya and a Malaya within the British Commonwealth led by people who, despite their opposition to imperialism, still share certain ideals in common with the Commonwealth ... if we [the returning students] do not give leadership, it will come from the other ranks of society.” Malaya, he noted prophetically, could be either “another Palestine or another Switzerland”.

Even before returning to Singapore, Lee had identified the strands necessary to make a successful politician with the aim of securing an independent, non-communist Malaya. The first was a commitment to greater social justice and income distribution. This was part of the ethos of the time, both in Britain, where Lee was involved with the Labour party, and with such exemplars of independence and social democracy as Nehru’s India. But it was also necessary politics. Lee believed that without a commitment to both anti-imperialism and socialism, radicals would win control of the freedom struggle.

The other element in Lee’s equation was multiracialism, which he saw as necessary to prevent Malaya from dissolving into war between two nationalisms, a Chinese one which was communist in sympathy and a Malay one which tended to be exclusive and feudal.

Back in Singapore, Lee the lawyer and Lee the politician were soon inseparable as he took up the cases of trade unionists, radicals and nationalists. Being from the British-educated Chinese elite, he had to work all the harder at being a leader to dialect-speaking Chinese and Indian union firebrands. His energy and application were prodigious, and he added fluency in Mandarin and Hokkien and passable Malay and even Tamil to his roster of languages.

He was the driving force behind the creation of the People’s Action party (PAP) in 1954, including within it people sympathetic to the communist insurgency, then at its height in the Malayan peninsular. The PAP adhered to constitutionalism while Lee acted for those detained under the Internal Security Act.

Lee’s fortunes as a politician benefitted from his bravura courtroom performances. It was this very success with juries that made him critical of the jury system. Judges were less easily swayed by emotion, and were appointed by the government. Once in power, Lee abolished juries.

Despite his advocacy on behalf of leftists and nationalists, there were those who believed he connived to ensure that the left faction did not get the upper hand in the PAP. The party, which had been seen as the main agent of constitutional development in Singapore, swept aside more conservative forces to win the 1959 election by a large margin. Lee became chief minister of a self-governing state within the Commonwealth, promoting social reform but retaining political detention without trial.

His principal objective became to achieve, in co-operation with the Malayan prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, independence through merger with a somewhat suspicious Malaya – which had been independent since 1957 – plus the territories of Sarawak and Sabah to form Malaysia. The PAP was divided on this and other issues and formally split in 1961, the left faction forming the Barisan Sosialis. However, the merger proposal was approved in a referendum.

Lee further solidified his position by mass detentions, including those of prominent Barisan leaders. Though he justified the detentions by reference to the lingering communist threat and Indonesia’s avowed opposition to Malaysia, they came to symbolise Lee’s authoritarian tendencies. With the Barisan decapitated, he won the 1963 election and the Barisan never recovered.

While unification made sense to the moderate majority of Singaporeans and Malayans, it soon ran into problems. Chief among them was the reluctance of the hyperactive Lee to play second fiddle to a Kuala Lumpur-based federal government led by the relaxed, aristocratic tunku, or prince. Lee insisted on the PAP trying to win seats in the peninsula itself, in the process setting itself up as the party more likely to protect Chinese interests than the Malaysian Chinese Association, the conservative Chinese element of the tunku’s ruling alliance. Lee made speeches which many regarded as racially inflammatory. Some Malays wanted him arrested. In the end, the tunku decided in August 1965 that the only way out was for Singapore to leave the federation.

One vision had failed. Now Lee redoubled his efforts to create a new vision – of a republic of Singapore with its own identity and national interests that could hold its own among potentially hostile neighbours. Malaysia and Singapore still needed each other. The Indonesian policy of confrontation ended with the downfall of Sukarno in 1966. However, times were difficult, exacerbated by British military withdrawal, which created additional problems of finding jobs for a rapidly expanding population.

The first 10 years after the expulsion from Malaysia saw Lee forge the society that is modern Singapore. It could have been done differently. Colonial Hong Kong, so similar in many ways, prospered as well without the guidance of a “philosopher king” or a “Moses”, as Lee was to be later described. Nonetheless, Lee was very much in charge of the new Singapore and thus deserves the credit, and the blame.

The ingredients included a dominant role for the state. This combined aspects of social democracy, for example in major efforts to improve health and public housing, with “the mandarins know best” attitudes to social and economic activity.

Foreign capital was relied upon to create jobs. This was a pragmatic recognition from the beginning that Singapore lacked the capital and knowhow to create industries. Meanwhile its entrepot role was, by definition, dependent on the services it could provide to foreigners.

Nationalism was fostered too, which meant infusing an opportunistic, multiracial commercial hub with a Singapore identity, sense of pride, citizenship and separateness. It meant having strong armed forces, a Swiss-style national service and international assertiveness.

For Lee, western notions of liberal democracy, free association, independent trade unions, juries and other aspects of the separation of powers might have proved an obstacle to achieving these nation-building goals. Yet he was well aware that the British had left behind some democratic expectations, and in order to compete economically, Singapore had to present itself to the outside world as a reasonably open as well as competently run state.

Some government intervention in the economy was simply pragmatic. But much of it had political overtones. The state, for example, created what is now the largest commercial bank, the Development Bank of Singapore, though there was never any lack of private ones. Its forced savings scheme was a colonial-eraprovident fund that was used to generate savings that helped give Singapore the best infrastructure in Asia. The scheme gave the government control over far more money than it needed, thus enabling it to dictate not only the pattern of investment but housing and consumer spending. The nation amassed huge foreign reserves, which underpinned its growth, reflected in a currency that was as strong as the German mark.

Emphasis on education, especially in science, helped Singapore develop as a base for multinationals. Lee’s government was very successful in identifying and fostering growth industries, whether it was the Asiadollar money market in the late 60s, oil exploration, production and refinery services in the 70s, or electronics in the 90s. However, critics – and even some government loyalists – noted a decline in the entrepreneurial spirit. Educated Singaporeans did not create enterprises: they went to work, very efficiently, for ones already created by foreigners, or the government. The administration was both extraordinarily pedantic and uncorrupt. Yet part of Singapore’s prosperity rested on it providing a safe haven for money made corruptly in neighbouring countries, smuggling or drug trafficking.

Intellectually, Lee recognised the importance of money-making. Money brought power. Yet he exhibited the kind of distaste for businessmen common among Chinese mandarins, socialists and intellectuals. Thus Singapore’s indigenous capitalists were kept on a short leash. From time to time prominent examples were made of “misbehaviour”.

For all its potential shortcomings, for all its dependence on the growth of neighbours, the rise of Japan and latterly of China, the reality is that for four decades from 1970 Singapore delivered economic growth rates almost as good as any in booming east Asia. There have been few hiccups. Thanks to the prosperity of its oil-producing neighbours, Singapore rode the oil crises easily. The mid-80s recession necessitated some minor policy adjustments, but generally, once the mould had been established, Singapore’s economic progress was as unruffled as its politics.

Internationally, Lee played a key role in the development of the Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean). At first he had been somewhat suspicious, fearing it could become a vehicle for Indonesian domination, or an expression of pan-Malay identity. However, he soon embraced it as an anti-communist buffer which linked countries with formal ties to the US (Thailand and Philippines) to the anti-communist but “neutral” Indonesia and Malaysia. Anti-communism cemented Singapore’s ties with the US when it badly needed implied protection as well as investment. With ties to Washington and Beijing, Lee helped to ensure that Asean participated fully in the cold war to force Vietnam out of Cambodia.

In practice, politics seldom stood in the way of business opportunities. After all, Singapore was commerce (not ideology) in action. But once the Soviet empire had collapsed, foreign policy emphasis changed to a wholehearted pursuit of economic goals. Again, Singapore was quick to see the advantages of turning Asean attention to trade, providing a new raison d’etre for the group. Freer trade was not just good for Singapore but for the region’s ethnic Chinese business community, many of whom saw Singapore as their spiritual home and salted away profits there.

In social as in economic affairs, Lee tried to shape society to an extent attempted perhaps only by Mao Zedong in recent times. What began in the early years as a voluntary family-planning campaign ended up with the state trying to influence marriage choices and “enhance” Singapore’s genetic quality by encouraging graduates to reproduce among themselves. Myriad rules, taxes, incentives and exhortations confronted the citizen. The result was an orderly society, but only marginally freer of crime than Hong Kong. It was a society where people were afraid to speak out. Lee the great debater was now the winner by default, whether in parliament or the courts.

While continuing with parliamentary elections, Lee muzzled the press, international as well as local, and stamped hard on opponents of the PAP. Opposition politicians were hounded by legal actions – often for libel, which Lee invariably won – and bankrupted. Social workers were branded as communists and detained till they confessed, often after coercive treatment.

Quite why Lee, revered as the father of the nation, found it necessary to use such sledgehammers was not clear. In the 50s, the communists were real and ruthless. But as time went on, real threats vanished. Yet the unrelenting ambition did not, and Lee was unable to change his self-image as a political streetfighter, the gang boss who forever had to prove his ruthlessness. Beyond that, he had a sense of insecurity about the future of Singapore after he was gone. Partly this was a sense that society would go soft with success, or, like the Malays, surrender to the easy languor of the tropics. The younger generation knew only success and the cultivation of wealth.

He, with his recollections of Japanese occupation, the expulsion from Malaysia, the potential threat from Indonesia, always imagined the worst. Singapore could not afford gentlemanly disagreements or real debates. The leaders led, and that was it.

Increasingly, there was only one leader. Comrades from the heroic anti-colonial days retired, drifted away or were pushed out – in the case of President Devan Nair in 1985, after a humiliating allegation of alcoholism that he contested. New blood was brought into the PAP, but increasingly it became a tightknit elite. It retained an effective command structure but the mass base eroded.

The so-called second generation had no real political experience but was full of intellectual accomplishment. Goh Chok Tong, who succeeded Lee as prime minister in 1990, was a competent and well-liked bureaucrat, but Lee remained in cabinet as senior minister. In 2004, Lee’s eldest son, Lee Hsien Loong, became prime minister, and his father “minister mentor”. He resigned from that cabinet position in May 2011 following an electoral setback when the PAP share of the vote fell to its lowest level since independence. He then took no further part in public life.

Goh had been unable to deliver the “kinder, gentler” Singapore that had been expected. The force of Lee’s personality, the moral authority that he commanded, left him the arbiter of anything he cared about. Like a Mao in miniature, he seemed both to enjoy and have contempt for the adulation that surrounded him. Never a tolerant man, he began to show some of the symptoms of age. International acclaim added to his convictions of his own brilliance and righteousness.

Some saw excesses of personal power, not just in his treatment of opponents but in the rapid promotion of his sons. The Singapore courts silenced a string of suggestions of dynastic politics.

With Goh and Hsien Loong minding day-to-day affairs, Lee was free to devote his energies to the world. He saw in the economic success of east Asia the triumph of “Confucian values”: discipline, order, respect for education and authority over western values of individualism, liberalism and democracy. He even succeeded for a while in promoting Singapore as the centre of “Asian values”. Lee was especially heartened by China’s economic success, defended its political repression and criticised Taiwan’s new-found democracy. China’s success fitted not only with his own philosophy but with the increasing emphasis in Singapore on its predominantly Chinese, as distinct from multiracial, character.

Ethnic prejudice lurked just under Lee’s image of technocratic rationalism. He combined assumptions about Chinese cultural supremacy with belief in genetic theories which influenced social policy in Singapore. But if Lee’s actions were sometimes driven by gut instinct, his head was more often the winner, particularly in international affairs. He could set aside his underlying distaste for America, with its crude culture and populist politics, and his Chinese ethnic sentiments to deliver masterly analyses of regional and global affairs. Only occasionally did he let prejudices get in the way of Singapore’s national interest – which, he clearly saw, lay with keeping US forces in the region.

Perhaps only he could succeed in making oppressive Singapore the main Asian critic of the US commitment to human rights and personal freedoms while ensuring that Singapore remained a key to the strategic plans of American military and multinationals alike.

Mostly – though not always – he could guard his tongue sufficiently to keep his Malay neighbours co-operative. His sheer length of service gave him a regional prestige that only Suharto could match, and his successors would not inherit. Suharto, with 180 million people and a vast archipelago to rule, had a big stage, while Lee gave every sign of regarding Singapore – with a population of 5 million in 700 square kilometres – as far too small for his talents.

Indeed, it was far too small. Its size accounted for his obsession that its every detail, down to choice of roadside trees, fit with his plans or prejudices, as well as his eagerness to advise larger countries on how to run their affairs.

Because of his background and early life, he could operate and dominate in many different milieus, but was totally at home in none of them. That perhaps accounted for his ruthlessness. He had permanent interests, not permanent friends. In sum, always a leader rather than a fullower, he set his own agenda.

Kwa Geok Choo died in October 2010, and Lee is survived by their two sons and a daughter. Lee Hsien Loong continues to be prime minister; his brother, Lee Hsien Yang, is chairman of the civil aviation authority; and their sister, Dr Lee Wei Ling, is director of the national neuroscience institute.

• Lee Kuan Yew, statesman, born 16 September 1923; died 23 March 2015

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/22/lee-kuan-yewGo to Healthwise for more articles

- for Lee Kuan Yew