August 23, 2017

By

In the remote forests of northern Sweden, Anders Svenningsson’s multiple sclerosis patients have benefited from a drug he’s been prescribing for the past eight years. It doesn’t require weekly injections, doesn’t leave patients feeling achy and feverish; and most important, halts their disease. That drug, Rituxan—originally developed to treat cancer—has become Sweden’s most prescribed medicine for MS, in which the body attacks its own central nervous system. Swedish doctors have great freedom to prescribe treatments they believe are appropriate, but few MS patients elsewhere can get the drug. That’s because its maker, Roche Holding AG, has never tried to sell it for the disease. Instead, Roche this year introduced a nearly identical medication that it markets under a new name and at 10 times the cost.

The tale of the two drugs highlights how pharmaceutical companies tweak aging medications to keep the profits rolling in. With Rituxan facing the expiration of its patent starting in the middle of this decade and another drugmaker due a share of the profit from the medication, Roche didn’t pursue it as a treatment for MS despite studies indicating it probably works. Instead, Roche invested in the offshoot medicine, which would take years to reach the market but enjoy longer protection against generics. That strategy began paying off in July, when the new drug, Ocrevus, wildly outperformed expectations in its first quarter of sales.

Stephen Hauser, a neurology professor at the University of California at San Francisco who led MS trials for both drugs, says the two have some minor differences. But doctors and patients must decide whether it’s worth buying Ocrevus, which he says is “10 percent more effective, 10 percent easier to administer, but 10 times more expensive.” Ocrevus runs $65,000 a year, while Rituxan costs about $2,400 annually in Sweden and $8,000 to $10,000 in the U.S. for patients who can get it prescribed for MS.

Roche argues that there are significant differences between Rituxan and Ocrevus. Because the newer formula is composed mostly of human genetic components, it has fewer side effects and patients won’t develop as much resistance to it, the company says. “Ocrevus was specifically engineered for long-term use in patients with chronic diseases,” says Daniel O’Day, head of Roche’s pharmaceutical unit.

When Roche decided to abandon Rituxan as a treatment for MS about a decade ago and focus on Ocrevus instead, “I felt it was immoral, because we had very good data” showing the older medication worked, says Timothy Vollmer, a neurology professor at the University of Colorado’s health sciences center. Vollmer says some insurers will pay for Rituxan, so he prescribes the one that will be cheaper for patients, because “I don’t have a reason to distinguish between them other than cost.”

It’s not uncommon for drugmakers to bolster their profits by reformulating medications and charging more for the new versions—though the companies always say they’re safer and more effective. Ocrevus is one of at least 10 MS drugs that have been revamped to boost their moneymaking potential, according to the Blizard Institute, a medical research center in London. Insulin producers have for decades made small improvements to keep prices high. Johnson & Johnsonin 2007 rejiggered an antipsychotic formula to extend its patent protection. And Roche a decade ago developed an eye drug similar to its cancer medicine Avastin but priced about 40 times higher.

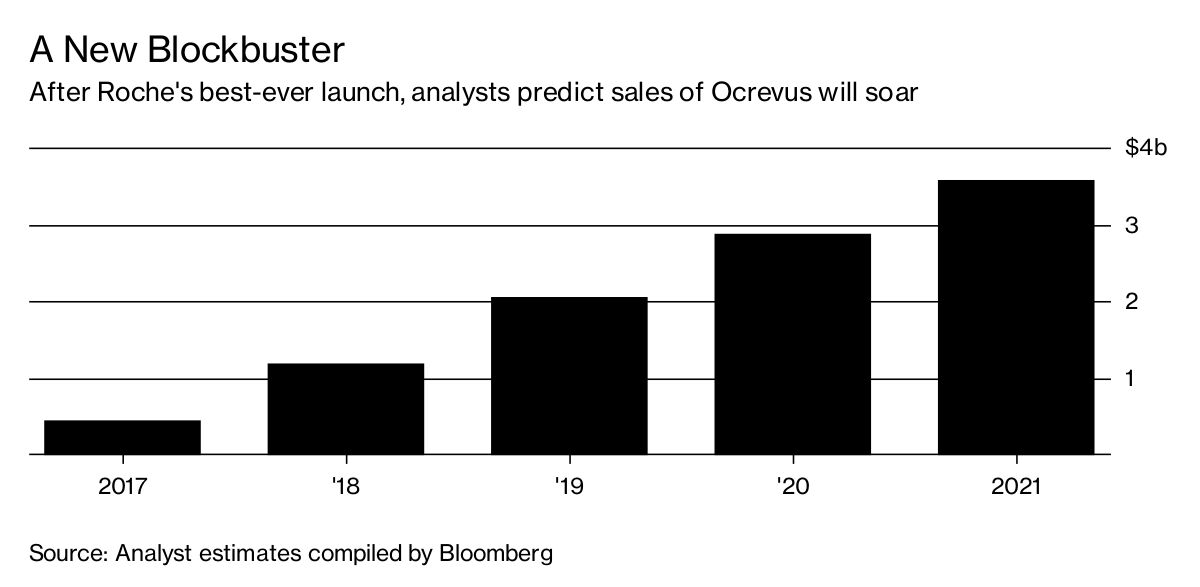

In the U.S., where the Multiple Sclerosis Foundationestimates that more than 400,000 people have the disease, neurologists have embraced Ocrevus. Since it got U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in March, Ocrevus has generated almost $200 million in sales, the best drug launch in Roche’s history. Approval in Europe is expected this year, and analysts predict it will top $3.5 billion annually by 2021. By contrast, Rituxan, which is widely prescribed for lymphoma, was never cleared for multiple sclerosis and probably never will be. A few thousand Americans with MS take the drug because their doctors prescribe it anyway.

Rituxan was among the first therapies to fight cancer by attaching to a specific protein. Its target is found on a type of white blood cell called a B cell. After it was shown to help people with various autoimmune diseases, researchers surmised it might also prevent the immune systems of MS patients from attacking the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. It was a new theory—doctors had thought another type of white blood cell played a bigger role—but the medicine worked. In 2007, a decade after Rituxan was first approved for blood cancer, a Roche trial showed that MS patients who took the drug had about 90 percent less scarring in their brains than people who took a placebo. Although a second study a year later failed in the toughest-to-treat type of MS, the results were encouraging enough to spur hopes that it would be effective for some of those patients, too.

Annette Langer-Gould, a former assistant medical director at Genentech Inc., the Roche biotech affiliate where Rituxan and Ocrevus originated, helped create a development plan for the two drugs. “How the medications work is exactly the same,” says Langer-Gould, now a researcher at health giant Kaiser Permanente, which has about 1,000 MS patients taking Rituxan. While both use proteins from humans and mice, she says, Ocrevus is “a little less mouse.” Genentech decided to push forward with Ocrevus mostly because the company could charge a higher price, according to Langer-Gould. Rituxan and other treatments for lymphoma were significantly cheaper than MS drugs, she says, but Roche couldn’t arbitrarily increase the price for cancer patients. Roche says the decision “was based on scientific and medical considerations so people with MS could have the medicine with the highest potential benefit.”

Even as Roche was backing away from Rituxan for MS, neurologists began to embrace it on their own. While running an MS center in the Swedish city of Umea, Svenningsson was impressed by trial results. He started prescribing Rituxan and saw a notable improvement in patients’ day-to-day lives. Some 3,500 Swedish MS patients take Rituxan, which has proved more effective than many rival drugs designed for MS, according to the Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish research center where Svenningsson now works. Unlike older treatments that cause flu-like symptoms and sometimes must be administered every other day, Rituxan is given via injection once or twice a year. “As patients got to the end of the trial, they said, ‘Please don’t give me back that old stuff again,’ ” Svenningsson says. “ ‘Let me continue with this.’ ” —With Susan Decker

BOTTOM LINE - Roche declined to pursue research showing cancer drug Rituxan can treat MS, instead focusing on an offshoot the company says is more effective—but costs 10 times as much.