By

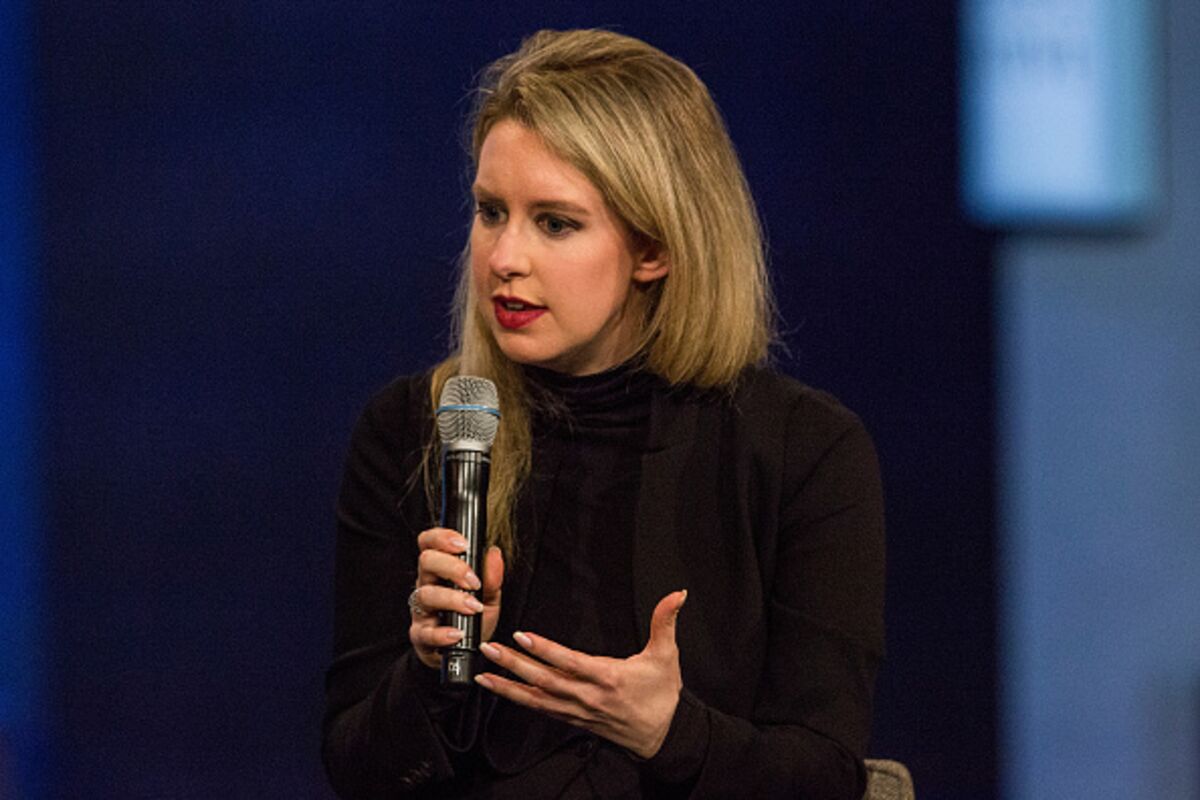

PHOTOGRAPHER: ANDREW BURTON/GETTY IMAGES

PHOTOGRAPHER: ANDREW BURTON/GETTY IMAGES

LISTEN FOR WHAT ISN'T SAID.

At just 32, she is the founder and chief executive officer of the high-tech diagnostics company Theranos, a startup valued at $9 billion that promised to revolutionize blood testing. Until recently, she was the world’s youngest female self-made billionaire. But her star image has dimmed quickly over the past year, and now Holmes faces lawsuits and a criminal investigation for possibly deceiving investors.

Still, she drew thousands to a talk at last week’s annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Chemistry, held in Philadelphia. There aren’t many celebrities in clinical chemistry, after all, and she may be the only one ever to be played by Jennifer Lawrence in a movie. And Holmes can tell a story people want to hear.

What’s needed to evaluate a talk like this is a combination of critical thinking skills – strong mental defenses against confirmation bias and subtle manipulation. Critical thinking would have helped investors realize much sooner that the company was headed for trouble. After all, they poured hundreds of millions of dollars into Theranos, though Holmes refused to explain how its revolutionary technology worked. Maybe they didn't know what to look for.

First, some background: Elizabeth Holmes’s fame was propelled by a remarkable, yet somewhat familiar story. She famously dropped outof Stanford at 19 to chase her dream of making the world a better place, and rose to helm a top Silicon Valley startup showered withpraise and venture capital. Journalists loved the narrative, and they loved her: Blonde and photogenic, and often clad in black turtlenecks (in homage to Steve Jobs), Holmes became a media darling. She was elevated in the tech press and profiled in the New Yorker in 2014, and even graced the cover of the New York Times style magazine.

But earlier this year, doctors published a study showing some of Theranos’s tests compared unfavorably to competitors’. Then, the company’s California lab failed an inspection by federal regulators. Not long after, the company had to throw out two years of results from its proprietary blood-testing machines. Now, Holmes is facing a two-year ban on owning or operating a laboratory. It was quite a rise-and-fall story (with the fall painstakingly chronicled by Wall Street Journal, whose reporters raised questions early on). Unsurprisingly,scientists were eager to hear what Holmes would say.

In her 90 minutes onstage, Holmes did not tell any obvious lies. Her genius was in the strategic leaving out of information -- creating holes that people tend to fill with faulty assumptions. Instead of lying, she prompted people to lie to themselves. Understanding how to avoid being fooled by this technique is important, given how frequently it pops up in fields far beyond science. Fact-checkers often don’t spot this brand of deception.

Onstage, Holmes looked polished in a masculine-cut black suit, showing no hint that Forbes recently adjusted its estimate of her net worth from $4.5 billion to nothing. And in a surprise to some attendees, she didn't talk about her company's troubles or problems with its previous technology, which she had dubbed the Edison machine. Instead, she devoted the session to a brand new invention: the “miniLab,” a medical-testing device.

On the surface, she sounded brilliantly technical (“The cartridge contains optical components for the range of test methodologies required to execute test orders designed to facilitate literal replication of protocol...” and so on for nearly an hour). She presented a video exposing the innards of this machine, which she said could do testing in molecular biology, immunology, clinical chemistry and hematology. It includes a centrifuge, a fluorescence microscopy platform, an isothermal detection system, a sonometer, a luminometer and a spectrophotometer. It was like a university hospital shrunk down to the size of a toaster.

You don’t have to know any of this jargon to spot the holes. How were these components different from existing technology? What could the miniLab do that current analytical instruments could not? She didn’t say. Which facets of this did Theranos researchers invent? She didn’t say. Did it work better than competitors? Who knows? She went into detail about a test for the Zika virus, but never explained whether it would be better, faster or cheaper than existing tests.

Holmes got some mild applause when an audience member asked if there was any evidence that giving healthy people more blood tests would result in better health. Holmes’s answer: “There are 9 million cases of undiagnosed diabetes.” That sounds compelling, but there’s a strategically placed space. Some might fill it with the assumption that her technology would be able to help those 9 million people -- folks who otherwise might be in danger of going blind or losing their feet. Don’t make that assumption.

She didn’t actually say there was evidence her company could help diabetics. Was there any? I tracked down Stephen Master, a professor of pathology at Weill Cornell Medical College who had prompted applause during the talk when he asked why Holmes’s new invention “fell far short” of what she’d been promising for years. The following day he was teaching a daylong mini course on big data, software and statistical analysis, along with Daniel Holmes (no relation), an associate professor of pathology at the University of British Columbia and head of clinical chemistry at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver.

I asked whether all those diabetics were undiagnosed because there’s a need for a more accurate or cheaper test for diabetes. Holmes and Master agreed the answer was no. And even if it were the case, they said, Theranos hasn’t demonstrated any improvement over existing tests. What about Zika? They said there are existing tests with better sensitivity than what Elizabeth Holmes presented. Dan Holmes said the miniLab was a reasonably novel arrangement of existing systems, worthy of one of the more modest parallel commercial sessions at the conference. Those sessions usually attract fewer than 100 audience members; with sufficient hype, they might get 200.

A few scientists expressed doubts about Theranos early on, and there are investors who steer clear of any medical company whose product or service hasn’t been tested and peer-reviewed. Some journalists, particularly at the Wall Street Journal. And perhaps more importantly, the skeptics paid attention to what wasn’t being said. It’s not enough to keep an eye out for lies. You need to remember to mind the gaps.

https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-08-08/lesson-of-theranos-fact-checking-alone-isn-t-enough

List of Theranos postings on this blog :

- Theranos: Scandal hit blood-testing firm to shut

- Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes indicted for alleged fraud, out as CEO

- The rise and fall of Elizabeth Holmes ...

- Lesson of Theranos: Fact-Checking Alone Isn't Enough

- A 31-year-old's fight to disrupt a $75 billion industry

- TEDMED: Elizabeth Holmes Lab testing reinvented

- Blood, Simpler: One Woman's Drive to Revolutionize Medical Testing

This post is on Healthwise